Today’s news is filled with stories highlighting the need for us to bring an analytical and critical perspective to reports we read about the election and to the statements and tweets offered up by the candidates. I agree. That’s why I’m always harping on the need for media literacy. Those analytical, critical-thinking skills are media literacy skills. So why can’t we seem to get media professionals, elected officials, education administrators and parents to understand the vital need for greater focus on media literacy education? Overall, we lack a coherent, national education policy on this.

This leads me to a related question: Does media literacy need a makeover? Those of us working in this field—and many more who simply care about media and its impact—are getting limited traction galvanizing folks around the need for media literacy for all. Often when I talk about media literacy, people don’t even know what I mean and I have to re-explain it over and over again.

It could be one of those Ambush Makeover-style reality shows, where we grab Media Literacy off the street and throw it in a closet for a redo on its definition, logo treatment and tag line. Or we could do it The Voice-style and have it parade itself in front of a group of media experts who would give it feedback on whether it’s being too pitchy or pushy, and how it needs to be clearer about its brand and style. Or we could follow it around for a few weeks, then edit together the most confusing bits and play them back while Media Literacy looks on apologetically, promising to change its ways.

A big reason media literacy needs a makeover is because of a misperception that took hold early in its life. Media literacy was put forth—by some—as a method to stop, or at least curtail, media use. Amidst concerns about the impact media might be having on people, children especially, some saw media literacy as a way to “inoculate” people against the evils of media. Some people and organizations implied or outright stated…etc.

—if you’re media literate, you’ll watch less TV.

—if you’re media literate, you won’t be swayed by advertising.

—if you’re media literate, you won’t believe the narrow gender representations

But nothing can guarantee that people won’t do something when they really enjoy it. Perhaps that’s a basic human frailty. The notion that media literacy competence will decrease media use pushes aside people who actually enjoy watching TV, playing video games, and even watching commercials! It implies that if you like those activities, you can’t possibly be fully media literate, because media literacy will wise you up and you’ll no longer be unable to defend yourself against the lure of evil media. Or so the logic goes.

If you’re a media company and you believe the goal of media literacy is to get audiences to consume less media, why would you want your audience to be media literate? This logic puts media companies and creators on the opposing side of those who care about media consumption and influence.

Trouble is, that isn’t the purpose of media literacy.

Media literacy is an eye-opener, for sure. But the purpose of media literacy is awareness, understanding, critical thinking, and creativity. As stated by the National Association for Media Literacy Education, “while media literacy does raise critical questions about the impact of media and technology, it is not an anti-media movement.” Media literacy encourages you to think about, analyze, consider, question, and create media. And then make a conscious decision about media use that’s right for you and/or your family.

Unfortunately, once that powerful anti-media message took hold, it’s been difficult to convince folks that the definition of media literacy is more complex and nuanced—and actually includes people that love to consume media.

As long as we approach media literacy as something that will miraculously decrease media use, we are destined to watch media consumption grow and media literacy be marginalized. If we really want to tackle this issue, we need to operate from the reality that for most people, media holds a beloved place in their daily activities, and in fact, there’s an overwhelming amount of media content that is exciting and entertaining, and even educational. I’m aware there’s a lot of content that isn’t. But it’s not media literacy’s responsibility to tell us which is which. It’s our responsibility as media-literate citizens.

I was prompted to think about this after reading a new report published by the Lagatrum Institute, written by Paul Copeland titled, “Factual Entertainment: How to make media literacy popular.”

I felt myself initially cringe at the notion of media literacy in a popularity contest. It would surely lose against sexier competitors like cyber-bullying, digital storytelling and propaganda. And yet, all of those are part of media literacy. Media literacy just isn’t as…well…popular. (Cue Glinda and a stanza of the Wicked song.) The truth is, since the term media literacy has been around for decades, people working in the field and others that care about the issue often call it something else so the issue seems new and it can get the attention it deserves. Talking about media literacy AGAIN can seem just so 1985. But it’s 2016 and we still haven’t found a successful way to motivate people around the need. Perhaps our present election will be the push it needs. The media has been an integral part of the story and our ability to understand how media is created, popularized, viral-ized, editorialized, and monetized is vitally important to our ability to comprehend the waves of information put forth in this election cycle.

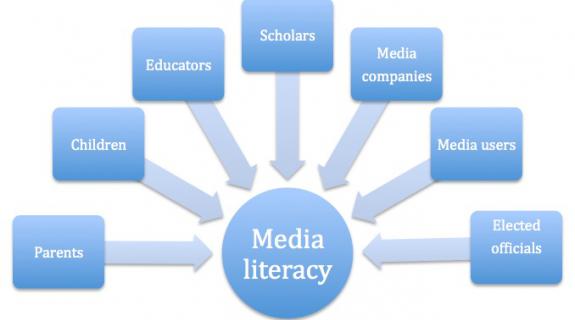

The way to embrace “popularity” in Copeland’s publication is to get media companies, like the ones you work for, to embrace it. Gotta admit, I like this guy. He keeps making points I’ve been making for years. I’ve always seen media literacy at the center of a wheel of stakeholders that includes parents, children, educators, scholars, media users, and, yes, media companies.

Now you see the need for the makeover…and we need your help. We need media professionals to embrace media literacy and help spread the news that it’s important for all of us to pause, reflect and act as good citizens in our daily participation with media.

Sherri Hope Culver serves as Director of the Center for Media and Information Literacy (CMIL) at Temple University where she is an associate professor in the school of media and communication. Sherri serves on the executive board of the National Association for Media Literacy Education. She regularly presents internationally on media literacy and children’s media topics. Sherri is co-executive editor of the UNESCO 2016 yearbook on Media and Information Literacy and Intercultural Dialogue and served as co-editor of the yearbooks from 2013-2015. She is author of The Television and Video Survival Guide and The Media Career Guide.

Tags:

__twocolumncontent.jpg)